The annual convention for Warframe, TennoCon, happened this past weekend. For those unfamiliar with the video game, it’s a space ninja looter-shooter with uncharacteristically benign monetization. Unlike other free-to-play games, Warframe ensures that all players can earn premium currency and has even removed microtransactions when players were using them too much. Between the lore and the game design, there are a lot of things I really like about the game that I want to pull into my own design. This post is an attempt to break some of that down into a useful analysis for the tabletop community; it should go without saying that spoilers abound.

Warframes

So what is a warframe? It’s sortof like a combat doll. It’s a construct that is piloted by an operator. The first frames were created by infecting people with biological mutations, turning their skin to steel and reforming their internal organs to become more resilient. While these mute soldiers worked for a time, their minds slowly degraded until they became little more than animalistic monsters. It was accidentally discovered that a group of survivors from a failed colony expedition (exposed to the mysterious Void) were able to tame and control the warframes using their powers. Some thousand years later, warframes are replications of these original frames, fabricated using blueprints and materials in a high-tech printer. They are still operated by those original survivors (called “Tenno”).

Just in case it wasn’t perfectly clear: the people who created warframes (the Orokin) were pretty terrible. They were a colonizing empire that did a bunch of slavery and genocide and most of the problems in the modern galaxy are because of things they did.

The concept of a warframe is incredibly interesting because it’s a weird intersection between Hero Unit and Class. A given warframe is based on a progenitor, and some of their personality influences all frames of that type. And yet — multiple people can inherit from that legacy at the same time, and the sight of a particular warframe might be more or less common. The narrative setup also means that growing in power is often a result of “self”-actualization or connecting with the personality of the warframe you operate, and trying to understand its desires. Many of the quests to unlock new warframes involve reconciling ancient injustices or fulfilling dreams.

Mechanically, each warframe has four active abilities and one passive abilities. In practice, this is sometimes expanded by giving one of those abilities multiple effects that the player can choose to use. Furthermore, the game allows you to feed a warframe to a big monster (called the Helminth), and then a single pre-designated ability becomes “stored” within the Helminth. The Helminth can then “subsume” that ability into your other warframes, replacing one of their existing four abilities with that stored ability. This is soft multi-classing.

There are 61 warframes at the time of this blog post. They are not slowing down.

So how does a game work with that many “classes”? Warframes are kindof “hero units”, but they’re clearly not individuals, so where is that line really drawn? Multiple players can use the same warframe in the same mission, unlike (for example) League of Legends which has 171 playable champions. If we compare in the opposite direction, the ttrpg DIE has a mere 6 paragons. How many archetypes are necessary to represent the full scope of player fantasy? Is there such a thing as too much? Let’s take a look at some of the warframes.

Hopefully this assortment sheds some light on how broad or specific a warframe’s “domain” can be. On the one hand, we have a very classic fantasy paladin through the Oberon frame. On the other hand, there’s the “I want to be a spider” warframe Oraxia. Both of these are clear and solid archetypes, but I’m not sure that traditional fantasy classes are going to fulfill the latter in any meaningful capacity. I think this ultimately comes down to player expectation (along with realism). Players want to roleplay as archetypes they expect to be present for the stories they’re expecting to play out. In traditional fantasy, those archetypes are often based on literature — ones like the fighter, the wizard, the rogue. Warframe has established its narrative such that players expect to play as mythological archetypes like Oberon or Sun Wukong (who is also a playable warframe). If you start thinking about classes as minor deities or mythological figures, it’s extremely easy to understand why Warframe has 61 and D&D has 13.

The other point I want to make is about how mechanical similarity can still feel distinct based on lore and supporting mechanics. Both Volt and Gauss are “speedster” warframes, able to use an ability that massively increases their movement. Volt is about being lightning personified, and has a strong elemental identity about throwing electricity, using an electric forcefield, or sending out shockwaves. In contrast, Gauss is more like a rocket; his ability doesn’t increase his normal movement, but rather propels him directly forward. The supporting abilities are also themed around the idea of converting energy between forms, turning movement into damage and stealing enemy heat (freezing them) to release explosive blasts. Personally, I would never be brave enough to release two speedster classes, but somehow both of these warframes are well-received and have their own devoted fans.

I think designers are afraid to design for specifics in some ways. If I wanted to play a brutalist, concrete-themed guy, many of them would point at a vaguely-relevant class and tell me that I should re-flavor and re-skin it to my heart’s content. I do think there is certainly a place for that, but I also think there is power in going all-in on a bit. Players asked the Warframe developers for a spider frame for years before Oraxia was released a month ago. Before then, “spiderframe” was simply a long-running community joke.

Factions

“Wait a second you just talked about factions last week.” Behold the seeds of my game design: borrowing stuff from other games.

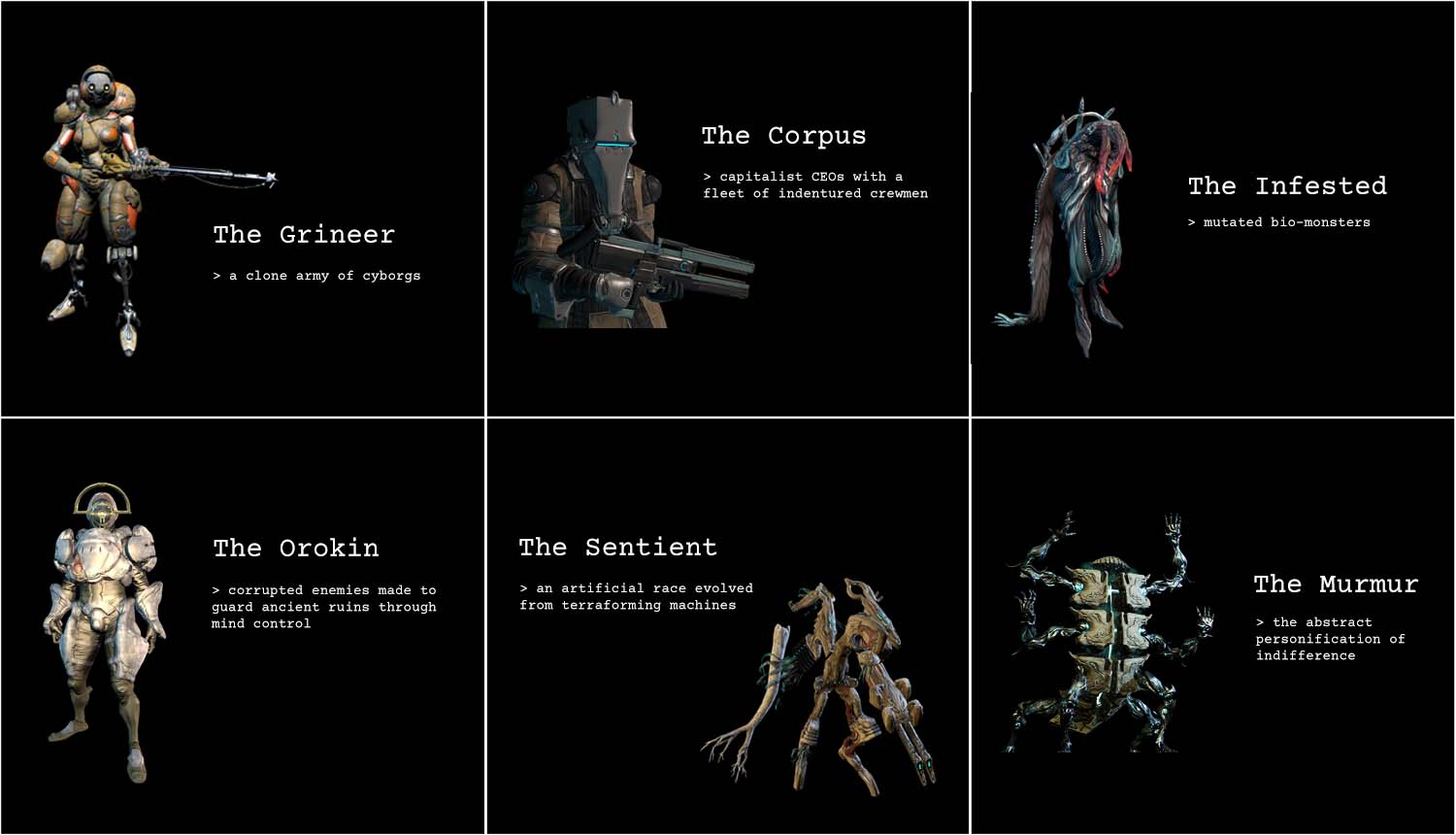

Fundamentally, factions are not that complicated. These are six of the most common enemy types present in the game, and each of them have a variety of units and bosses that the players fight. Each enemy has health and shields visible to the player, along with a hidden amount of armor. They have weapons and attack patterns and support abilities. So what are our tabletop takeaways?

- Recognizable enemies form the building blocks of combat puzzles

When players are able to identify an enemy and predict their behavior, it immediately establishes the basic combat puzzle of priority management. For example, the Corpus employ hover drones that provide bonus shields to everyone nearby. By targeting those drones first, it reduces the effective health of the enemies in the vicinity.

- Vulnerabilities create build variety and reward preparation

Each of these factions have their own elemental vulnerabilities and resistances. The Grineer are weak to Impact and Corrosive damage, and they take reduced Heat damage. While players frequently create “builds” — specific loadouts of weapons and modifications — optimized to deal the maximum amount of damage in general-purpose scenarios, it is often advantageous to create a build for a specific faction. Doing so often requires much less investment of resources than a generic build by exploiting those inherent vulnerabilities.

- Faction-specific weapons are cool and good

I just think they’re neat.

You should be able to take the plasma rifle from the guy that’s been shooting you and use it yourself. This applies to fantasy games too. Let me take heretic flame staves or demon swords and use them.

- Most importantly, factions enable a level of macro narrative

Obviously this is not new to tabletop roleplaying games. Systems like Beam Saber have robust faction mechanics, but many games are simply not paying attention to why enemies are doing things. If you ask the question “Why are these enemies here?” and the answer boils down to “They live here.”, I think it should be a signal to step back and reflect. Fighting random-encounter slimes in the middle of a field is somewhat boring. Alternatively: going into the troll cave to kill them and take their stuff says a lot about the characters you’re playing and the macro narrative you’re spinning.

The Corpus crewmen are extremely interesting, because they are vividly contrasted with other indentured NPCs, who are actively working to resist their leaders and sabotage their plans. One of the coolest moments in the game involves stepping into the shoes of a lone crewman who defies orders to save lives, placing humanity above profit. I want to see more games take advantage of the stories you can tell with enemy factions.

What do you think? Am I onto something with ttrpg classes or do these ideas only work in a game with hero units? Have I convinced you to think differently about enemies? Let me know your thoughts in the comments.