I’ve been working on some organization lately by putting together a library of all my tabletop games. Part of that process involves trying to come up with a “pitch” for each game — a brief summary on what the game is about and what makes it different from any other given game. Sometimes this summary was easier to write based on my own familiarity with the game, but I found that the better games began with a declaration of purpose. The first paragraph of the first page of Blades in the Dark immediately establishes what the game is about and what the “player promise” is:

Player promise is a game design term I use to refer to what fantasy the game tells the player they will be able to embody. Sometimes the fantasy can be big and complicated, or it can be as simple as “you’re a mech pilot and you can fight other mechs”. In this particular case, Blades sets player expectations through some very specific wording: a criminal scoundrel has a different weight than an adventurer in another fantasy game.

In comparison, it takes Coyote & Crow roughly 346 pages to explain the player promise:

There are many things I like about Coyote & Crow, but the book opens with (very important) worldbuilding before going into the character creation section, followed by the core mechanics and then GM advice. “What do the players do?” is seemingly an afterthought, as if the reader is supposed to intuit that from the worldbuilding and character abilities. As someone with a large ttrpg library, it’s difficult for me to understand why I should use Coyote & Crow for a given story instead of any other rpg system. Outside of an interest in running C&C specifically for its own lore, the book did little to give me a reason.

As I was considering this, Adam Seats published a thought-provoking post over on their blog about media illiteracy in tabletop games. Very specifically, it is the case study of how Wanderhome and Ryuutama are both “nature-focused, travel-focused games with easy-to-learn mechanics” but very different goals and vibes. Many people recommend them in the same breath without examining what sets them apart. As Adam explains, Ryuutama is about characters that Do Great Things — worthy of a story-eating dragon — and Wanderhome is about characters Being themselves on a journey unconcerned with ending. The differences compound with deeper study: i.e. combat is present in the former but forbidden in the latter.

While I wholeheartedly agree with Adam: people should be more media literate, I can’t help but feel that designers should work from our end to help players understand the games we make. This is not a stance that I hold every game to; some games are definitely meant to be opaque art pieces and deciphering them is part of the fun. However, for games that are really meant to be played, I think it is in the designers’ best interest to explain their expectations, goals, and player promise — ideally at the beginning of the book. Doing this gives context for everything that comes after.

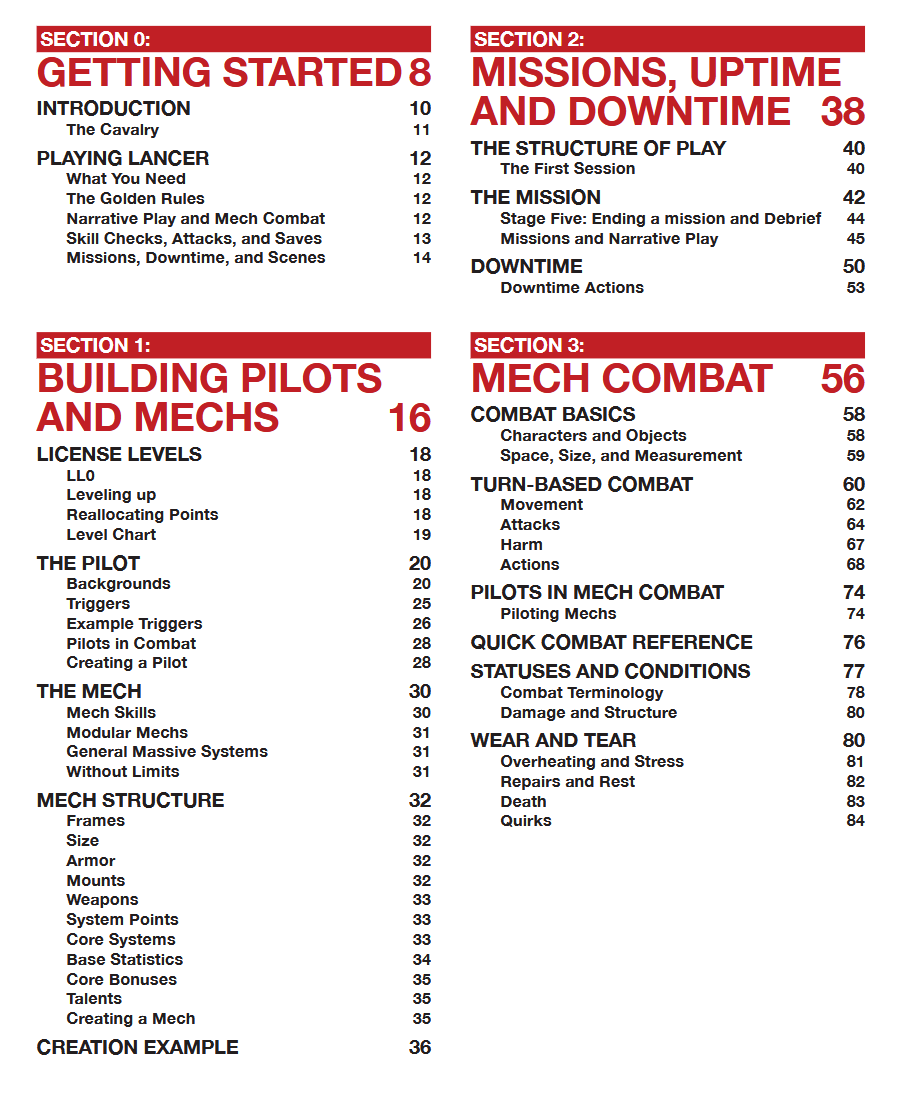

I began to expand the scope of my musing beyond just introductions and into the structure of an rpg in general. One of the larger debates I’m aware of is whether or not to put character creation before or after core mechanics. I think this ultimately comes down to what type of game you’re making — is it more about the blorbos you can play as or the what the system lets you do. I am specifically concerned with The Serket Hack and how I should be putting together its structure. Even more specifically, I’ve been thinking about what a vertical slice would look like — a bare bones pre-ashcan edition of the game with just enough substance to test that the basics work before I develop all the classes and extra features like crafting.

- Introduction

- Macro game loop

- Character creation

- Combat

- People to fight

My first instinct is to follow suit from Lancer and frontload the character options, because that’s one of the most exciting parts. Upon reflection, I think it’s useful to give more runway to the premise so that players know what the characters are going to be doing. “Macro game loop” just means talking about the wuxia format — the separation between society and the wilds — and character progression being tied to individual listed feats rather than the accumulation of currency. Devoting an entire section up front might be ambitious, but at the very least, it’s something I want players to be thinking about as the examine the classes.

How should a ttrpg be structured? Is it really necessary to explain what the game is, or can you depend on readers to already be invested? If this ramble has helped spark insight, let me know in the comments!

2 Comments

Strong thoughts on the concept of player promise, one I had almost forgotten. The idea of what to frontload the player with (self-expression vs world-expression) in retrospect now feels like it should be an obvious framing device of player-expectations.

I am somewhat confused by the concept of wuxia in this way, do you mean the growth or progression path?

There are a few ways that Wuxia is an influence on The Serket Hack, but in this particular instance, I’m talking about:

1) Character growth (attaining power) as a direct motivator for action rather than an incidental “you happened to have gained enough XP / milestone to gain new class features”.

2) Players leave towns to go into the wilderness in search of that power (or for other reasons), and then return. This forms the macro game loop in the same way that in Blades in the Dark, the players’ macro loop is going on heists and then into downtime.