I hang out with a lot of OSR folks. It’s where I’ve found community, and it’s where I perceive the most discussion happening in the ttrpg space. The blogging culture is thriving and it feels like people are talking with each other rather than posting to an audience. Unfortunately, despite the excellent work Elmcat is doing, I can feel pretty isolated from other people who play games the way I do.

The communities that exist are divided in a way that I don’t fit into easily. From what I can tell, most people either fall into the OSR camp or plant their flag on a specific game that they make their identity. “Trad” isn’t really a community but you can find plenty of D&D players or Call of Cthulu players with blogs about those games. You can find the (excellent) Lancer pilot.net or even discords based around a specific designer/publisher. That doesn’t make them a “neo-trad” community, and trying to live between the bubbles is more difficult than settling in with the OSR bloggers, who maintain a relaxing code of system agnosticism even if they claim B/X is lingua franca when they write stat blocks.

All to say: I get hit with the Blorb Principles a lot when I talk about prep work and the process of running games.

I have no idea when Idiomdrottning came up with Blorb but it’s frequently cited as one of the load-bearing concepts behind the OSR. It’s technically part of a family of playstyles, but the others are mentioned far less frequently and they operate more like siblings than quadrants on an axis. The core concept of Blorb is this: your highest priority as a DM is depicting an objective game world. I needed to write my defense of the quantum ogre before I could tackle Blorb because building any kind of anti-Blorb position relies upon reacting to the players rather than sticking to a pre-defined plan.

This post is…scaffolding. I wrote my manifesto early in the year and I’ve had plenty of time to think since then. I’m waiting further still before I publish a new edition but I want to talk through my ideas about being anti-Blorb in a post-trad play culture.

prep scenarios and scenes

The term “scenario” is loaded with history and context here. Japanese game developers began using it as a loanword from the film industry to describe the plot of a game. Over on Bluesky, Nickoten has an incredible thread filled with interviews and translations relating to the history of scenario writers in Japanese games. This term was also used by tabletop game writers, notably in the GM section of Sword World, which would go on to influence Ryuutama and Fabula Ultima in turn. Let me quote a couple of sections from the fan translation of Sword World 2.5:

The GM should describe the scenario briefly, as it is merely a taste of things to come. You should clearly communicate the purpose of the scenario to avoid problems with meandering and dilly-dallying.

However, if a player blatantly goes against the spirit of the scenario, the GM should politely but firmly guide and advise the player to follow the scene. Even though each player has some independence as to how their character acts, they shouldn’t actively bring the level of excitement down for everyone else.

Conversely, the GM may secretly change the content of the scenario if they think that an unexpected turn of events would make it more interesting.

Admittedly, I am not deep in the trenches of the Japanese ttrpg scene; however, in the research I’ve done, most of these games are designed around a play culture where sessions do not happen frequently and it’s important to not waste everyone’s time. There is a sense of focus where players will meet and play through a capital “A” Adventure with a beginning, three acts, and a conclusion. You can see this in the Ryuutama worksheets, which are provided to help the GM plan out the literal Act 1, 2, and 3 main events and sub events. Ryuutama scenarios are subdivided into specific types — Travel, Gather, or Fight.

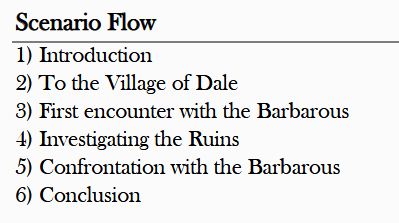

Despite the way all of this sounds incredibly scripted and railroad-y, I want to emphasize that these scenarios are the set-up to an adventure and not its resolution. Let’s take a closer look at the example scenario in Sword World 2.5:

The players are given a quest to exterminate some Barbarous near the village of Dale. The introduction scene establishes this premise by having the guildmaster approach the players with the request from the village’s headman. This is followed by an uneventful journey to Dale, but the players arrive to find that the village was attacked at daybreak, adding pressure to their quest to find the Barbarous lair. Whenever the players leave to try and find the Barbarous, they encounter a patrol first with a short combat encounter. Following the tracks of the patrol allows the players to find the ruins they’re using as a lair, and remaining stealthy allows them to find multiple entrances. Finally, the main combat at the ruins inevitably happens and the players are rewarded for their efforts.

Building a scenario flow like this is essentially prepping the path of least resistance. Nothing here is essential to the scenario besides the main objective of Barbarous extermination. It’s extremely easy for a GM to adapt to player decisions and let them bypass a patrol with good stealth or lure the main Barbarous force into a trap outside of their lair. Weaving the scenes into a scenario like this is essentially the last line of defense where things will happen if the players don’t have any clever tricks or fail to take action. It’s also certainly possible to fail the objective — the players might be defeated by the Barbarous — but the scenario should be constructed so that outside of a refusal to engage, the players cannot fail to find the adventure itself.

throw paper after seeing rock

There are two ways I interpret this. The first is the humble quantum patrol. It doesn’t matter what direction the players leave Dale to search for the Barbarous. If they go looking, they will find the patrol in that direction.

The second is a more literal attempt to challenge a player by targeting their weakness. In my Fabula Ultima game, Farmer Gadda is playing a classic knight character that does a lot of counterstrikes. Because I know this, it affects my encounter design, and I can challenge him by creating flying or ranged enemies unable to be hit by his melee attacks. However, throwing paper means I am vulnerable to any player that throws scissors. Our friend Magnolia has levels in sharpshooter and a gun perfectly suited to dealing with any such ranged opponents. This is a classic combat puzzle, but the concept applies to non-combat situations as well.

make your world reactive and collaborative

The hierarchy of truth in Blorb prep prioritizes whatever you’ve written before the session, whether that’s specific notes or a mechanical system like rolling on a table. I believe in doing the opposite: the most important truth is the one that is based on the fiction taking place. For example, if the players let one of the Barbarous goblins escape with a leaked plan about scouting the ruins, it would be more interesting for the main force to plan an ambush outside of their lair rather than the pre-written confrontation on the interior.

Delivering on player agency doesn’t stop at character actions. It creates more interesting stories when the authorial pen is shared generously. If a player asks “Is there a chandelier in the room?” it costs you nothing to add one even if it wasn’t in your notes. Letting them drop a candelabra on unsuspecting enemies is just cool.

non-diegetic information

Give your NPC’s quest markers.

I’m serious. I’ve been thinking about this one for a while. When I ran a Lancer campaign it was pretty easy to keep things diegetic by presenting missions as freelance contracts posted on the omninet. That was a convenient narrative tool, but it also kept things fairly cyclical: players would get a job, do the mission, and repeat. Being able to accept and work on multiple quests simultaneously opens up the sandbox by making the choice of destination more difficult. Plotting travel routes to chain together quests becomes a macro-scale puzzle — and it’s all made possible by being up-front with your players about what quests are on the table. For my Fabula Ultima game, I’m going to tell them “hey there’s a guy here with a quest.”

The broader principle at work here is the idea that the GM should be communicating more information on the meta-game layer rather than trying to signal through the fiction. Pursuit of immersion at any cost creates a needless amount of bloat in the process of decision making. Without understanding the consequences of a decision, you spend time formulating a prediction before deciding between your own guesses. Nothing feels worse as a GM than when a player decides against an interesting choice because they talked themselves into believing it would have a rotten outcome.

This style of play is not diametrically opposed to Blorb. I think there are underlying commonalities — an idealized internal consistency is one of them. Once you establish something, it’s important to fairly adjudicate the consequences. Where I differ from Blorb is my hunger to tailor a game around players. That doesn’t mean that they should always win, but that they are the protagonists and prime movers of the setting. If the story isn’t about them in some way, then why are they playing those characters instead of someone more relevant? If we’re not engaged in an interesting scenario, then why are we wasting our time? I do not find value in the immersion of an uncaring game world.

2 Comments

Very interesting read, and its getting me to go read your previous post about quantum ogres (which is also very good so far)

Maybe eventually I will have more formulated thoughts, but I do agree that what you are talking about is not completely opposed to Blorb. I find it really helpful to have a better framework other than thinking in terms of full Blorb vs complete rewritten plot or “play to find out” games.

I’m afraid I have to disagree here even more strongly than I did with your Quantum Ogre post; it feels like you’re misrepresenting blorb – even strawmanning it?

The first principle is (https://idiomdrottning.org/blorb-principles)

> Never Prep Plot

> Blorb is a prep-focused playstyle, and prep is central, but never prep plot.

>

>Do prep entities. Places, enemies, friends, items, rewards. Porte-Monstre-Trésor.

>

>What happens should be emergent, not prewritten. Events should be things that might happen (from mechanics, dice rolls etc), not always will happen, or, worse, that the DM could choose to have happen.

*Absolutely* the goblins can plan an ambush outside their lair once they become aware of the characters’ proximity. The goblins’ course of action emerges from the events of play, not relying on the pre-written plan of an ambush. That plan is only loosely held; you haven’t committed to it in advance as “the plot”.

But I’m not keen to get into Fabula Ultima / JRPG style, except as a source of inspiration for very other forms of play, so maybe you’re speaking to a different audience.