In a game where every character can participate in commerce, what is a merchant?

Every character can pick up a sword or steal, but fighters and thieves are established archetypes. We could conclude, then, that a merchant is someone particularly skilled at business. This perspective is both reductive and conceptually boring: stories of business are generally less exciting than battles and heists. There are obviously plenty of workplace narratives, but why does the merchant archetype appear in fantasy games next to wizards and warriors? Fundamentally: what is the player fantasy being promised? In order to understand, let’s look at some merchants in games.

Ryuutama

Classes in Ryuutama each come with three skills. The Merchant has Well-Spoken, Animal Owner, and Trader.

Well-Spoken provides a small +1 bonus to any Negotiation Check. Animal Owner increases the amount of animals you can bring on a Journey without paying daily food and water. All characters can bring one animal for free, but the Merchant can bring up to three. Finally, Trader allows the Merchant to buy items at a reduced value and sell them at a higher price under specific conditions. In order to activate Trader, the Merchant has to buy or sell at least four items of the same type at the normal price and then roll a check. If they fail the check, then they must go through with the transaction at the normal price; if they succeed, the roll determines how much value is gained.

The core of this class is built around that last skill, which is designed around the idea of buying a large amount of goods at one village and then selling them at a different village. Using this ability allows successful merchants to earn money easier than other classes attempting to do the same. Pack animals can be used to carry items between villages, and Well-Spoken provides a bonus to the Trader checks.

It would be an easy mistake to end the analysis here: the accumulation of wealth is often the end-goal of many characters and players. “Number go up.” The unspoken second half of Ryuutama’s merchant requires us to examine the surrounding context of money in the game. What can you spend money on?

Ryuutama is defined by travel; it is a game about journeys. Managing food and water is a central mechanic, and the quality of those supplies influences the journey. Niche items like umbrellas and walking sticks provide bonuses depending on the weather and the terrain. Money governs how well the party is equipped to travel, which can make all the difference at the end of the day. In this way, the merchant is best compared to a utility class like a wizard.

Octopath Traveler 2

Despite my best efforts, I haven’t played every Japanese roleplaying game yet, and the limitations of my experience constrain the examples I’m able to point towards. I’m going to talk about Octopath Traveler 2 because I’ve played it, but I want to stress that this is hardly the first — or even the most notable — game to have a merchant class. The earliest game I’ve found with a merchant is actually Dragon Quest III in 1988, which was the first game in its series to introduce a vocation system. It’s easily possible that earlier video games had playable merchants, and I welcome anyone with information to chime in the comments.

The merchant of Octopath Traveler 2 is Partitio, a man hailing from a destitute mining town with an oath to destroy “that devil called poverty”. His story centers around bringing prosperity to towns, culminating in a deal where he trades eight billion leaves (the octopath currency) for the rights to the steam engine, preventing it from being monopolized by the wealthy. Mechanically, Partitio has the ability to purchase items from NPCs and hire them into the party. These hirelings can be called upon in battle a limited number of times, but they also provide indefinite passive effects, such as discounts on purchases or increased value when selling. The hiring mechanic is also used in a handful of quests where you need to take an NPC with you to another location — such as reuniting lost lovers.

In battle, Partitio’s skills revolve around resource management. He can donate “boost points” to other party members — a universal resource used to empower abilities. Additionally, he can sacrifice his own skill points to distribute them across the party or deal special attacks to receive money or job points based on the damage dealt. These abilities make him one of the most powerful support units in the game, but I actually want to talk about one of his side quests and what it implies for merchants in general.

Partitio gets three unique side quests called “The Scent of Commerce” where his instinct for investment unlocks game features. The first one involves Partitio recognizing the sigil of a retired legendary merchant, and he solves a riddle to trade for the merchant’s records — a manuscript full of lore the player can read. The second one has Partitio invest in a brand new invention: the gramophone. This causes all of the taverns in the game to gain their own gramophones, where the player can listen to the game’s soundtrack. Finally, the third and most important: Partitio purchases an unfinished ship as a sign of faith in a shipwright’s apprentice, which later allows the party to sail across the sea and access new parts of the world.

If we “zoom out” from looking at merchant abilities in the micro, there’s something here in the Scent of Commerce. Merchants are capable of undertaking projects of scale that would ordinarily be inaccessible to most archetypes. Buying a boat is almost a half-step towards domain play, and it falls into the “large project” category like forming an organization or disaster relief.

Fabula Ultima

This is actually the reason I wanted to write this post. While my play test of Fabula Ultima with the Paper Cult crew is still ongoing, our last session was really excellent and I wanted to give some special attention to the merchant class and reflect on what the merchant fantasy is about.

Everyone in Fabula Ultima has access to a resource called Inventory Points (IP) which functions similar to Load from Blades in the Dark: you can spend IP to declare that your character has a particular item. In direct contrast to Ryuutama, Fabula Ultima assumes the players generally have everything they need and allows you to retroactively have unexpected items. By default, players restore their IP by paying money in towns to stock back up on goods.

Four of the five Merchant skills revolve around Trade Points, which are almost the premium version of IP. Merchants can gain TP by resting in an area where commerce is possible or once per session when they “help an NPC or community defeat greed and corruption, improve their quality of life, or coexist with other creatures“. Trade Points can be spent to gain information, produce rare items and materials, introduce new NPCs, or to ignore IP costs.

So far, Fabula Ultima’s merchant follows the previous examples as a class that specializes in resource management and utility / support. Its abilities are more helpful than you might otherwise think because players are forbidden from sharing IP between themselves, but the merchant’s trade points can allow other players to ignore IP costs, making it the only class that can pay for other people’s item use. However, it’s actually one of the merchant’s unique heroic skills that caused me to introspect:

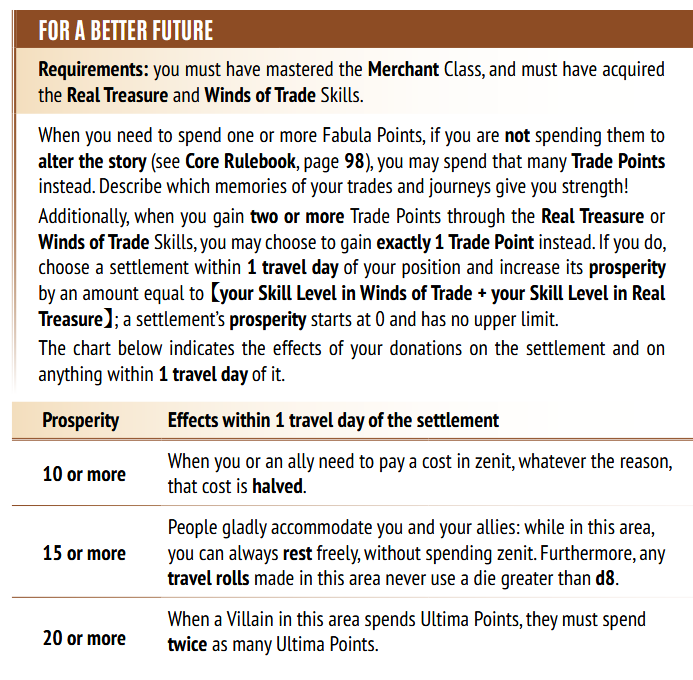

I actually took this skill on a whim because I forgot to level my character until the last minute and I maxed out the ranks of my merchant class first. It ended up fitting perfectly into the narrative I was building around my character, and when we played, it made a huge impact on our game.

Essentially, For A Better Future allows you to forfeit the Trade Points you gain to increase a settlement’s prosperity. The level of a town’s prosperity gives it up to three powerful effects from halving the monetary cost of anything in the region to doubling the price of a Villain’s powers. I think it was Astral Frontier who said that it “completely changes the type of game you’re playing” and I agree. Suddenly, the merchant has a tangible mechanical way to increase the prosperity of communities and it rewards players for establishing bases and hubs to operate out of.

The fantasy merchant is a utility class based around supporting your party with items rather than spells. They’re good at talking to people, and they usually involve internal resource management to maximize their effectiveness. Merchants often work on macro scales, forming the catalyst for large projects or communal change. A successful merchant brings prosperity to the world around them, and it’s important to reflect that in the narrative by treating settlements as more than a backdrop for downtime. Almost an inverse of the typical dungeon crawler, the merchant’s challenges lie in the marketplace, while their benefits are reaped when the party leaves town full of supplies for the road.

Now go put a merchant class in your game for me, because I love playing this archetype.