I’ve been reading Fabula Ultima and playing Octopath Traveller 2.

Somehow, these two ingredients have mixed in my head to develop a dungeon crawl procedure based on their chemistry. Neither of them are really about dungeon crawling, and I am, perhaps infamously, not an OSR nerd. This is why I find it so weird that a dungeon crawling procedure is bouncing around in my head, and I’m a little excited about it. I am probably reinventing the wheel here, but I’ve never seen this procedure codified before, so it’s new to me. In essence, I am applying the Fabula Ultima core rules for overland travel into a smaller scale, with some twists for personal taste.

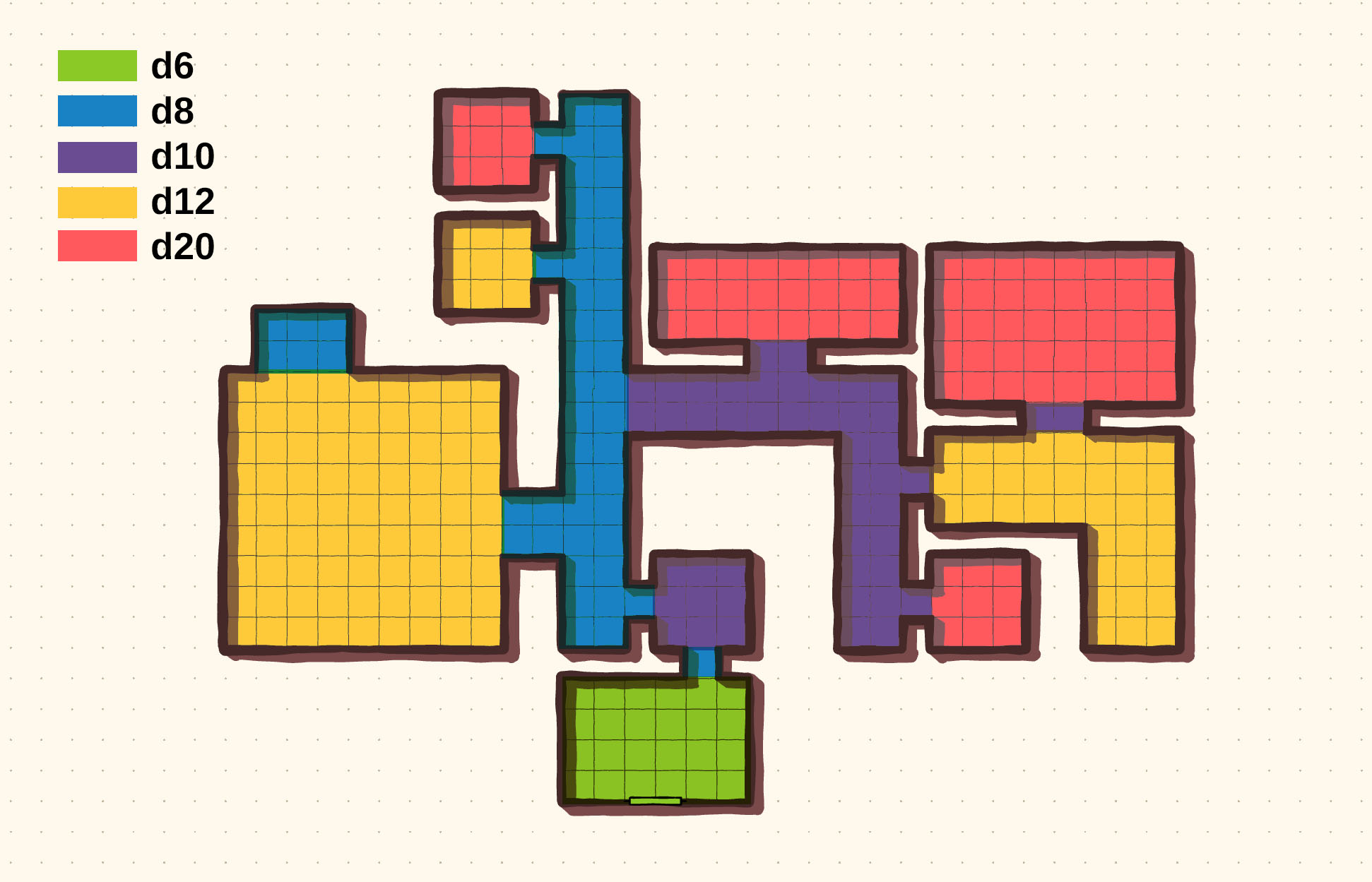

the platonic ideal of a dungeon:

The players are represented by a single token avatar for their entire party. Time spent in the dungeon is divided into turns. Each turn, the party may move as a unit a number of squares equal to their speed — let’s say five spaces as an example. This movement is restricted to orthogonal motion (no diagonals). After this movement, the GM rolls a die corresponding to the highest danger level of spaces traversed during the turn. If the number is six or greater, the party has an encounter. If the number is two through five, the party discovers something about the dungeon or the room they’re in. If the number is one, the party discovers loot.

In the demo dungeon above, moving five spaces in the green entrance would mean rolling only a d6. On the other hand, moving from the green room through the blue hallway into the purple vestibule would necessitate rolling a d10. This color-key exists for the GM’s eyes only — the players are unaware of the specific boundaries between threat areas, but you should endeavor to describe the vibes of each area well enough for the party to make informed decisions.

One important note is that discovery and loot can each occur once per room, so as to discourage players trying to game the system by walking back and forth in an easy zone. The discovery and the loot should also be scaled somewhat to the room in question. Entryway loot might just be a novelty trinket, but loot from a red room deep in the dungeon could be a magical artifact. The discoveries are intended to be “neutral” outcomes used to add flavor to the game and provide interesting color rather than the primary mechanism for getting actionable clues.

dungeon actions

After movement and resolving the consequences of the die roll, the players are free to take as many dungeon actions as they desire. There are three basic actions I’m envisioning, but more could be added as necessary:

- Recovery

This is a broad action that covers anything the party can do “to” themselves, by themselves. Eating all of the cheese wheels in your inventory to recover health is an example. Casting spells to heal wounds is another. Coating your knife in poison also applies, even though that’s not really “recovery”. I should get a better name for this category.

- Survey

The players make some kind of group spot check as dictated by your system of choice. For sake of demonstration, let’s say that this is a simple die roll of a d20. There are four points of interest within the room with difficulty levels of [5, 3, 10, 16]. The players roll an 11. In this scenario, the GM reveals the location of the first three points and also states that there is a fourth undiscovered point.

The players cannot take the Survey action again on this turn, but they may choose to stay within the room (resolving any die results) for another turn and Survey next turn. Doing so will automatically reveal any undiscovered points from the initial Survey.

- Interact

You might be wondering what “points of interest” are from the previous example. This is a catch-all term for anything players can interact with. It could be a chest of loot or a self-destruct button. It might be a secret passageway or a jukebox. Notably, the GM can always place obvious interact-ables in the dungeon that don’t require a survey to spot, like NPC merchants or large doors.

considerations & juice

Time does not pass while the players are stationary, which is a bit of a double-edged sword. Players can’t set up camp and rest to recover resources inside the dungeon, nor can they wait for reinforcements or anything else that requires time. However, they’re also not going to bleed out while standing still, and there are no wandering monsters that will attack them while they deliberate plans.

The system is deliberately set up to have levers for expanding the design. A thief-type character might subtract a modifier from the party’s movement die by keeping everyone more stealthy. A bard-type character might increase the party’s overall speed, allowing them to cover more ground. Encounters from this system easily feed into a small depth crawl, with more dangerous encounters resulting from higher numbers rolled. However, I would probably create a pool of enemies based on the different zones in the dungeon. Slimes should be more common near the entrance, but robotic sentinels should be the most common near the science lab further in.

It also goes without saying that this dungeon procedure is very “combat as sport”, and encounter frequency should be tailored based on the average length of combat. As an idle thought, it would be interesting to build out a system where combat becomes abbreviated the more you encounter an enemy. I want to abstract the concept of a party that has to fight through many battles, but I don’t necessarily want to watch every battle play out at the table. Anyway, that’s a blog post for another day.

two final notes

The dungeon is always illuminated. You don’t get hungry inside the dungeon.