Gather with me around the fire as I bring you another tale of Meet the RPG. The night is cold and there are spirits moving in the darkness, but perhaps the story will bring some warmth to our tired bones. I was joined once more by my compatriots in the Paper Cult to play a new game and experience what it had to offer. This time, we played Legend in the Mist, a new-ish RPG by Son of Oak.

The game describes itself as “rustic fantasy” which is obviously different from “low fantasy” or “natural fantasy”. The precise taxonomy is somewhat up to personal opinion, but my general understanding of the genre at play is: “what if we set a fantasy game in the Appalachian wilderness?”. Player characters are unlikely heroes from small mountain villages and everything beyond the hearthfire is dark and shrouded in mystery. Dangerous spirits older than the dirt stalk the forests and should you encounter them, you might find yourself bargaining your memories to save your life.

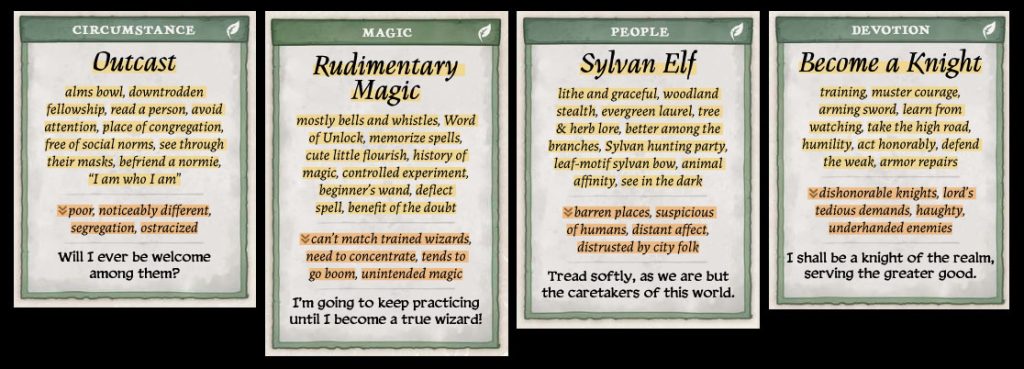

Mechanically speaking, Legend in the Mist is not a complicated game. Characters are a collection of tags. They have four major groups of tags, called themes, in addition to circumstantial story tags or even item tags for significant objects. The book provides a lot of guidance for building themes, including broad categories for them like “Personality” or “Devotion”, and it’s easy to make a character by simply choosing from the themes and suggested tags in the text. If you’re feeling daring, it’s also just as easy to come up with your own theme or tags from scratch.

These are example themes from the book, spanning several categories each. Each item highlighted in yellow is considered a power tag, while the orange ones are called weakness tags. While there are a few different core resolution procedures depending on how detailed you want to get, the basic premise is that you roll 2d6 and then add the number of relevant positive tags minus the number of relevant negative tags. You or the narrator may choose to invoke a theme’s weakness as a negative tag, and you might also have a relevant negative status to detract from the roll’s power.

It’s elegant.

When we played it, we compared it to FATE multiple times. Though it’s been years since I played, I remember the struggle of trying to break a character down into an appropriate collection of skills, stunts, and aspects. Legends in the Mist cuts everything down to a single atomic unit and gives you a clear procedure for building a character.

I like the game. I also have a few bones to pick.

“””rustic fantasy”””

You might have noticed the flaw in having such a broadly applicable system immediately. As far as I can tell, nothing on a mechanic level supports the rustic fantasy genre. I haven’t played Son of Oak’s other game — City of Mist — an urban fantasy noir RPG, but if it’s built on the same Mist Engine, I think these books are more like setting guides for a generic game.

The book has examples and suggestions for character themes, but the presented lists are merely suggestions. In the character creation process, the book says that the simplest method is to just think of four themes and write them down. Themes have “quests” attached to them to represent their narrative arc and guide milestones, but that’s hardly an aspect exclusive to the fantasy genre.

As a matter of point for our game, I took it upon myself to create the warframe Yareli:

I played as an apprentice priestess with water magic and a flying ride-able manta ray companion with a devotion to freedom. It worked surprisingly well.

Everything was obviously flavored for the rustic fantasy setting of the starter adventure (Heap-Thing of Skunk Glen), but all of that flavor was simply something we as a table decided upon. The book’s mechanics are just as happy to see me play a bio-mechanical surfer idol.

anti-expressionism

Anyone unfamiliar with Jay Dragon’s Expressionist Games Manifesto should go read it. I’ll wait.

Not every game should be expressionist and I don’t even know that I would strongly associate my ideal games with expressionism. However, there are some things just stick out to me more now that I’m looking at games in this post-manifesto world.

Legend in the Mist doesn’t shy away from telling you how your character is feeling. On page 18 in the tutorial comic, one of the consequences is getting a Pang of Remorse tag added to your character sheet — and we’ve firmly established that characters are just collections of tags. During our games, one of the first things that happened to my character was getting into a fight with a village elder in front of the whole town. As a consequence, my character got a status tag to show that I had been embarrassed.

At the end of the session we had a discussion and I communicated that getting told how my character feels was uncomfortable for me. Not in an “I need a safety tool” kind of way, but the sort of discomfort you get from trying a new food and discovering you hate the flavor. We ultimately decided that status tags should have a negotiation before affecting a character’s interiority at our table. This worked great and I never had an issue for the remainder of our sessions, but I don’t think it’s something built in to Legend in the Mist.

the arms race

In my heart of hearts, I am not a story gamer. Semantics are an eternal battlefield, but I like games with an abundance of formal rules to interact with and mastering their mechanics. Rules maximalist vs. rules light. I write this preface to acknowledge that my issue here can very much be dismissed with “it sounds like it’s not your type of game”. That’s true. Your mileage will vary based on the people at the table. With that said, this game has an arms race problem.

In the final confrontation between our plucky band of misfits and a trash spirit, my character applied a whopping 12 power across three themes and burning one story tag. This was lowered to 9 power due to a difference in tier, but I rolled a total of 15 and nuked it. I felt a little bad for doing so, but my character’s build happened to perfectly align with the situation at hand, and I had an absurd amount of relevant power. I had intentionally been invoking my weakness tags as much as possible in order to improve my themes, allowing me to have two additional power tags by the end of the game.

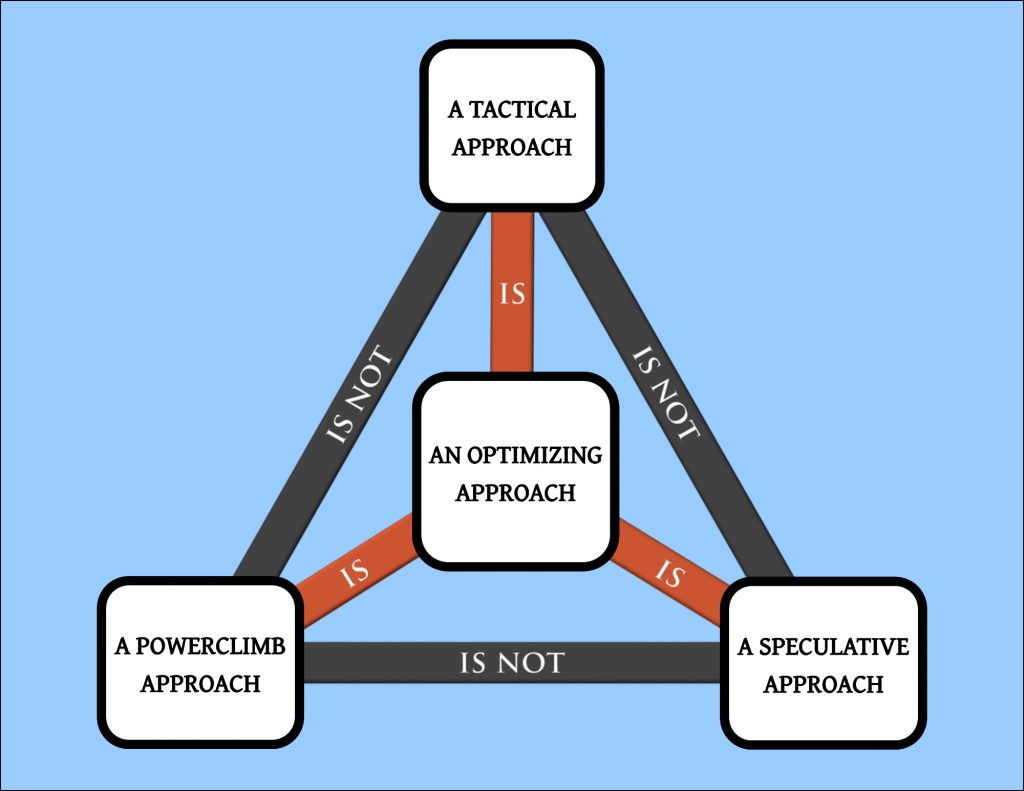

(diagram by Levi Kornelsen)

I like optimizing games and I have a penchant for power fantasy. I’m the kind of gamer who will grind three hours to be overleveled for a bossfight that takes three minutes.

The only advice the book has to offer for narrators with powerful players is to raise the difficulty and consequences for failure. By assigning more negative statuses, you can counter a player’s critical mass of power tags. Better yet, the book advises, simply give them challenges they don’t have the tools to deal with.

Balance is entirely arbitrary, and there are no hard rules for guidance. Even if this is a narrative-centric game with a collaborative approach, I think this is a very dangerous stance to take. I can easily see it making the game un-fun to a lot of players.

I think the game is extremely elegant, and a worthy successor to the FATE legacy. There are many tables who will enjoy playing it, and the book is fantastic for building rustic fantasy characters.

I like Legend in the Mist.

I would not choose to play it again unless asked.