Last night, the Paper Cult crew wrapped up our Fabula Ultima game. Out of every game I’ve played with them, this is the game I regretted saying farewell the most. I’ve decided it’s my favorite fantasy game and it probably competes with Lancer for being my all-time favorite some days.

It’s been a weird 48 hours since then. First, Valeria dropped an incredible review of Fabula Ultima. Beyond having played more sessions of the game, she brings some important context to the table: Ema has been pretty vocal about her design intentions. Without seeing some of the discord screenshots, I would not have intuited quite how much Fabula Ultima is a game designed around sharing top-down narrative control.

Second, Clouder published another blog post talking about his experience trying to make a dungeon in Fabula Ultima and how his instincts were at odds with the design of the game. If we look at dungeons in Japanese roleplaying games, they are hostile locations with key items and bosses. From a TTRPG perspective, these are specific narrative beats rather than random treasure and encounters. As seen in Valeria’s screenshots, Fabula Ultima is designed with quantum ogres in mind; whatever path the party takes, they will still find the ogre boss waiting for them. This leads to a set of rules that encourage linear dungeon building, which is the antithesis of how Clouder builds his games.

I wanted to preface this review with those two blog posts, because my thoughts today are very much in conversation with them.

let’s talk about the campaign

We started as always with a session zero. My other three comrades were already veterans of Fabula Ultima, so this Meet The RPG was purely for my benefit. As seen in my recent Appendix N post, I come from a background of Japanese roleplaying games and anime. I pulled the name and appearance of my FFXIV character and made an Underworld Apothecary. At the end of character creation, my classes were:

- Merchant 3

- Floralist 1

- Tinkerer 1

Characters in Fabula Ultima have an Identity, Theme, and Origin. These are the three core traits that define a character. You can use meta currency called Fabula Points to invoke them and reroll dice. Unlike many other fantasy games, you do not have one class and your classes do not define you. My character wasn’t a Merchant with some Floralist and Tinkerer, she was an Underworld Apothecary with skills from Merchant, Floralist, and Tinkerer. Taking levels in a class allows you to get one rank in a skill from that class.

Despite the level distribution, my character’s main focus at the start was using the alchemy skill from Tinkerer to create randomly determined potions. Merchant is a support class that allowed me to spend an alternative currency to create those potions, and Floralist gave me a way to restock my supplies during battle.

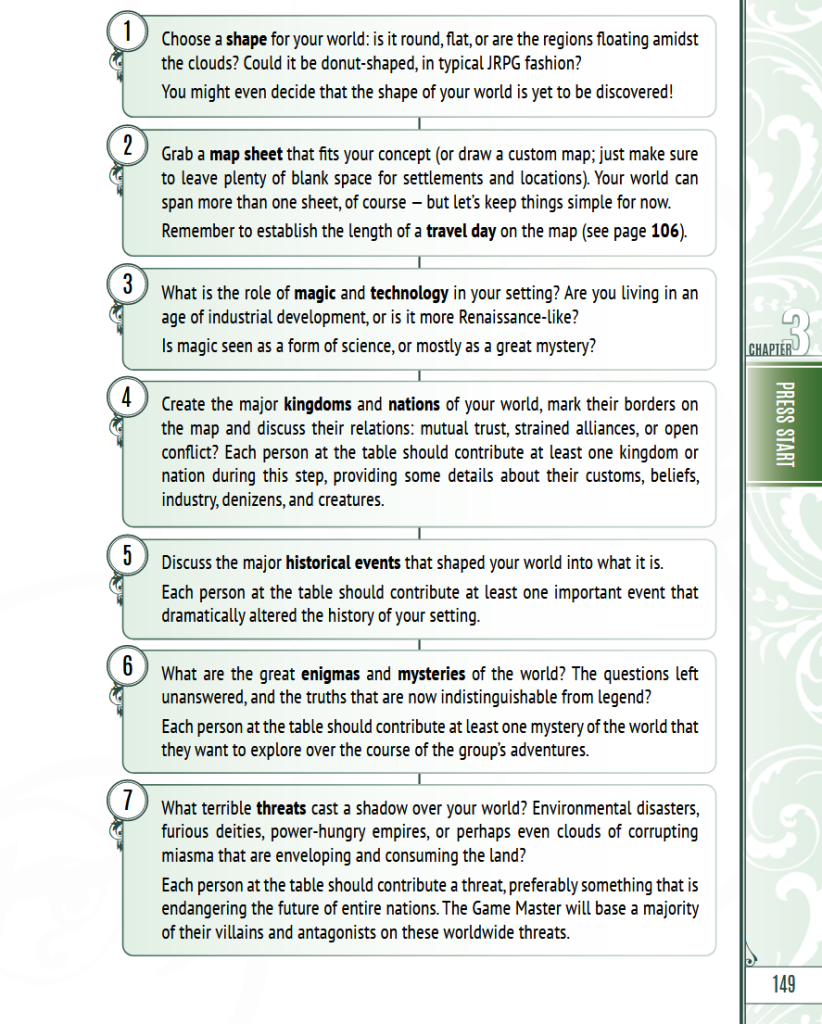

More importantly, during session zero, we walked through the world creation procedure for the game.

The game emphasizes that each person at the table (including the GM) should contribute kingdoms, historical events, and mysteries. Building the setting is a collaborative effort and ultimately a discussion between all players at the table. This is something baked into the game from session zero.

Together during session zero, we painted the broad strokes of a fantasy world in turmoil. The Land of the Sun engaged in ruthless conquest while the Lesovik Sultanate profited and the Archipelago Alliance was caught in-between. Rumors of a demon army attacking villages on the outskirts contrasted mysteries of an ancient kingdom of gold that vanished after discovering forbidden alchemy. All of these things are plot points created by players at the table rather than a preconceived campaign put together by the GM. Similar to the palette grid, this process helps get everyone on the same page about what we want the campaign to include. Notably, presenting these ideas was not a dictation: everyone at the table contributed and suggested details to flesh out the concepts and tie them to each other.

This sort of thing is why Valeria describes Fabula Ultima as “a storygame in trad drag”.

There were three sessions of gameplay after session zero. Fabula Ultima games begin at level five, and many skills have potency increases at levels 20 and 40, so we played at those breakpoints. Outside of an abbreviated dungeon crawl in the first session, most of our time was spent engaged in big picture narrative play or experimenting with combat. I don’t believe this is representative of the game as a whole, merely our priorities in experiencing the game. Fabula Ultima doesn’t have any special procedures for how to handle dungeon delving or socializing, so spending time on those things wouldn’t particularly help us understand the game.

combat

Despite having a vast amount of skills and character options, the combat in Fabula Ultima is pretty streamlined. Each player takes a single action on their turn and that’s it. (I’m ignoring a couple of skills that let you do something extra based on specific conditions.) Battles are fought in classic Japanese roleplaying game style:

Everyone stands in a line while they try to kill each other.

One of the things I found interesting is that despite being a Dice Game, most of the time nobody misses. There are no skills that give you flat bonuses, and only a couple skills that increase your die size. Some weapons are more accurate than others, but not by a large amount. In the final battle, the villain hit me every time it attacked and I hit the villain every time I attacked. Only party members who had seriously invested in defense were missed by the villain occasionally. This might be my bias because of the way I built my character, but it seems like the game is designed around recovery and mitigation more than avoiding hits entirely.

narrative play

I want to clarify specifically what I mean by “big-picture narrative play”.

The Land of the Sun had a giant floating island with a solar laser it was using to herd the rampaging demon army towards their enemies. This was the scenario presented to us by the GM in its entirety. Being the heroes of this story, we decided we’d confront them head-on by going up to the sun laser and breaking it. To do that, we needed to find a way up there and then we’d need to fight some people probably.

At this point, my character was level 20 with the following distribution:

- Merchant 10

- Floralist 1

- Tinkerer 6

- Wayfarer 3

As part of reaching level 10 with Merchant, I mastered the class and selected the heroic skill “For A Better Future” which allows you to improve the prosperity of settlements you rest at. Higher prosperity gives you many benefits, including a 50% reduction in cost for anything you do while you’re in the area of effect. One of the interesting developments over the course of the game was that my character naturally fell into a leadership role because I told the GM I wanted to create my own organization. I had small dreams at first — just a handful of members dedicated to keeping people safe and investigating mysteries. It was my own riff on the Scions of the Seventh Dawn, called the Harmony of Coral.

When presented with the obstacle of how to reach the doomsday weapon, my character was in prime position to build a custom airship, using the Tinkerer project class feature supplemented by my Merchant heroic skill and assistance from the Harmony of Coral.

The conversation where we figured this out was done almost at the metagame level, where we as players pitched ideas to one another before deciding what our approach would be. It reminded me of talking about an engagement roll in Blades in the Dark. The game is unconcerned with tracking days or material components or making skill checks to see how fast you make the project. Building an airship is simply something that my character was capable of, because I built her that way, so when we needed one it just happened without any dice rolling.

killing god

I have less to say about the third and final session of our campaign. We played at level 40, ten levels below the level cap for Fabula Ultima. At the end of the game, my character was:

- Merchant 10

- Floralist 2

- Tinkerer 10

- Wayfarer 3

- Symbolist 10

- Entropist 5

The purpose of going to level 40 and killing god, for me, was to really understand what the game looks like when you reach high levels. If you look at something like D&D 5e, the game becomes sluggish and the stories you tell must be of a certain scale just because of the things you have access to.

In Fabula Ultima, every class is mastered at level 10, so being level 40 just expanded the scope of what we could do — not our damage output or relative power. We fought god because it’s a fun trope in Japanese roleplaying games, not because our characters were nearly demigods ourselves.

I took 15 levels combined in Symbolist and Entropist because they were classes that synergized with what I was already doing: supporting, buffing, and debuffing. More specifically, Symbolist already uses the Inventory Points that my character was built around and it has access to a unique heroic skill called Ritual Seal, which allowed me to perform a ritual and store it for future use. In the final battle against the Engine of Eternity, I used the sealed ritual to stop time and allow the party to rest in the middle of the fight. During the time stop, we were also able to speak with the goddess and demon king to learn why the cosmic powers conspired against humanity, which ultimately allowed us to chart a new course for the world where people could determine their own destinies.

taking a step back

That’s a lot of campaign to digest. I wanted to walk through my experience from the game so that you can see where my thoughts come from and how I got to where I am. Having said all of that, I want to talk through the important things I think about the game:

- Mechanical complexity without operational complexity

- Self-expression rather than role fulfillment

- Shared authorship at the table and high trust environment

- Scene-based approach

I talked briefly above how combat didn’t slow down at level 40, and that’s one example of what I mean by operational complexity. Despite having a large amount of meaningful options, the core gameplay of Fabula Ultima is incredibly straightforward. You roll two dice and compare it with a number. You get one action per turn. Complexity comes in the form of “should I spend my turn studying the villain or placing a barrier on the party?” or even “should I attack with fire because the enemy is weaker to it, or should I use an earth spell that also inflicts a status effect?”. To some people, this sounds like analysis paralysis, but there’s less penalty than other games due to how quickly the rounds move. I also found it trivial to write myself some notes ahead of time to remind me of general tactics and plans.

Role fulfillment is something I was thinking about after Valeria called Fabula Ultima a storygame, and I started comparing it to something like Apocalypse World. Instead of picking a playbook like the Angel or Battle Babe, you get to decide what you’re called in Fabula Ultima. Characters are a collection of skill levels tied together by an identity, theme, and origin. There are no restrictions on what you can be or evolve into. One of the issues I had with Break!! is the way a Sneak could never learn to cook — the game had strong opinions on the type of character you could be as soon as you picked a class. Fabula Ultima is almost the opposite of that. You can even start the game as a wizard and take a bunch of fighter skills so by the end of the game you have a completely different identity. I can’t think of another game where I could tell that story of a wizard school dropout who decided to get really buff and hit things.

Another degree of separation from what I typically consider “storygame” is the way they adhere to the mantra “play to find out what happens”. I think it’s a good ideal, but I enjoy a little more narrative authorship and Fabula Ultima gives that to me. I like being able to add my own people, places, factions, and events to the world and watching how they interact with the story. That’s part of the reason I GM games, I think, because I want to see my ideas in the fiction. Obviously this requires a lot of trust, and it connects to one of Valeria’s criticisms about Fabula Points. These points can be spent to add details to the fiction and in turn, instantly solve many problems. I think it says something that none of us in the Paper Cult game ever used them for that. We spent them many times for rerolls, but I think we were more excited to try and solve problems with tools like rituals and projects and the GM gave us enough freedom to add things to the narrative without spending Fabula Points. All to say: the game expects you to share authorship, so I think your mileage may vary wildly depending on your table.

The last thing I want to talk about is how important “scenes” are to Fabula Ultima’s design. One of the main pieces of advice to GMs is to “think cinematically”, and it reminds me of Clouder’s blog post about dungeon design. Instead of trying to design a dungeon as a physical location, I think Fabula Ultima wants you to design a dungeon by thinking about what scenes you want to happen in the dungeon. There can be choice and variation in that — despite what Ena said in the discord screenshots, not everything has to be quantum ogres all the way down. But Fabula Ultima makes more sense to me when I think about the game in terms of scenes instead of locations or units of time.

I’m a designer because when I play other games, I find friction points and think to myself how I would change it or make it more appealing to me. Fabula Ultima is special because when I read and play it, I don’t find myself wanting to improve it. The only thing I want is more of it.