I can hear it now.

“Serket! You literally reviewed a game last week. Why do you have another review for an entirely different game this week?”

Timelines are funny. The PaperCult crew wrapped up our game of Break!! on the 28th and it took me two weeks to find time to write about it. Directly following that game, I was scheduled to run Salvage Union. As it turns out, we knocked out session zero last week and finished the first session yesterday. After playing, we decided that we had sufficiently Met The RPG with just the one session. When you boil everything down, Salvage Union really isn’t that complex, but I’ll elaborate on that soon.

I had another topic lined up to blog about, but I’m pushing that to next week because Salvage Union is really fresh in my mind and I think it’ll be good to get everything on paper.

overview

Salvage Union is a game about salvaging scrap in the post-apocalypse as a mech pilot. It is directly based on Quest RPG, which is a simple d20 system. The fundamental mechanic is this:

| Roll | Result |

|---|---|

| 20 | Outstanding success. You get what you want and more. |

| 11-19 | Normal success. You get what you want. |

| 6-10 | Tough choice. You can get what you want but there will be a complication unless you give up. |

| 2-5 | Failure. You don’t get what you want. |

| 1 | Bad failure. You don’t get what you want, and a consequence happens. |

Players start by making a pilot, which can be one of 6 core classes and eventually evolve into 5 more hybrid classes. These range from Engineer (good at fixing stuff) to Cyborg, which combines the Hacker and Soldier classes. Each class specializes in something useful like repairing, fighting, or even just carrying large amounts of cargo. As time progresses, the pilots can train during downtime to unlock a tree of relevant abilities.

After building a pilot, players are given 20 scrap to build their starter mechs. Each mech has a unique chassis ability and stats, and you add systems (hardware) and modules (software) to customize what they can do. Some of these are as fundamental as a locomotion system while others are more niche, like floodlights. The amount of systems and modules on a mech are limited by the available slots on the chassis, and some components require you to spend Energy Points or gain Heat to activate.

Finally, players collaborate to design their Union Crawler, a mobile base / village that the pilots operate out of. This crawler functions similar to a party/squad/gang sheet in other games, providing abilities and a shared identity for the pilots. The upkeep and upgrade costs for the crawler serve as a macro incentive for the pilots to go out and find more salvage.

this is just a dungeon (all the way down)

While it never uses the term explicitly, Salvage Union takes a lot of cues from the OSR. It establishes “rulings not rules” as a core philosophy, and advises mediators to use the Information Choice Impact Consequence schema when distributing information.

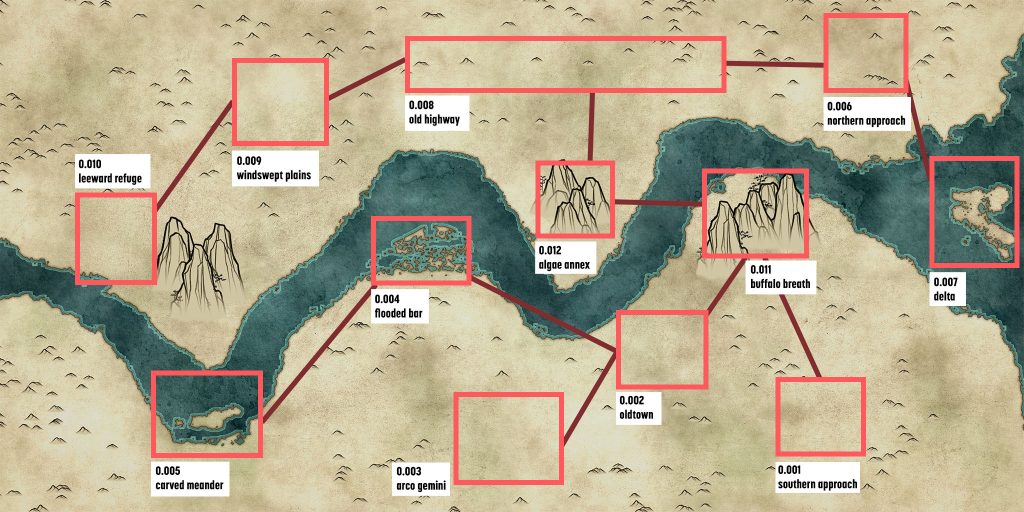

What I found during my prep for the game is that the advice and mechanics converge to guide mediators in creating a fractal dungeon. Salvage Union is designed around campaign play, and establishes three levels of maps for the players to explore. The campaign map is a point crawl between regions. Each region is a point crawl of areas. Areas can either be single zones or further broken up into a point crawl themselves. Pictured above is the region map that I created for our game.

The basic game loop revolves around going out into the wasteland to salvage and then returning to the crawler when your cargo hold is as full as you can make it. A minimum amount of pressure is applied to the players through the crawler’s upkeep system, which requires scrap based on its technology level to keep it from breaking down (and losing abilities). This directly mirrors the fantasy dungeon-delving loop of exploring for treasure and returning to town to sell and restock on supplies.

A key difference is that Salvage Union is far less constrained than a traditional brick-and-mortar dungeon. Pilots can basically leave whenever they want, and unless there’s external circumstances in play, nothing stops them from taking as long as they want on their salvage runs. The lack of hard walls also means that players can try to “shortcut”, like fording the river instead of using the bridge. There are dangers to doing so, but the option to try contributes to a feeling of freedom.

dice and consequences

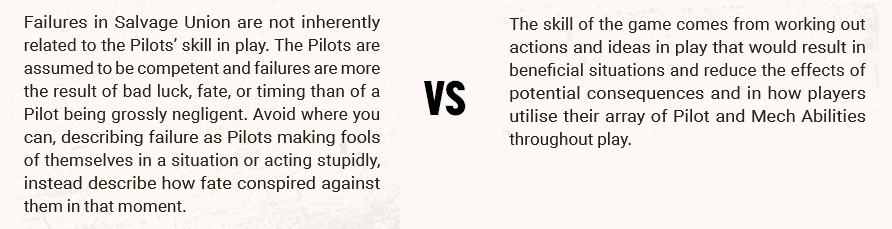

The most defining thing about Salvage Union is the way it handles rolling dice. Any time the player rolls the dice, it is treated as a test of fate — not player skill.

At first, I assumed this was simply “good GM advice” that’s common enough to see in many ttrpgs. Over time, I gained an understanding for the full implications of this design.

There is nothing players can do that will give them better odds.

This runs counter to many players first instincts if they have any experience at all with ttrpgs. We are trained to bargain and position the fiction and stack bonuses — but there are no bonuses. There is no advantage or disadvantage. Nothing the players do will give them a +1 to the roll or a lower DC. The core mechanic is simply all there is.

Instead, the purpose of positioning and creativity is to influence the consequences on a failure. For example, my players were trying to smuggle scrap past a corporate toll, so they made a plan to send an empty mech for them to inspect while the other two sneaked past. If they had rolled poorly, the consequences would have landed on the player with the empty mech, but the other two would escape with their precious cargo. As it happens, they rolled well and no consequences were needed, but that was the moment the system really clicked for me.

it’s pretty forgiving

When I was doing my prep, I was really worried because I come from an alt/trad background and I want to perfectly balance my encounters and build neat little combat puzzles. The book is also pretty vague on how much salvage to place in the map; it mostly explains that more scrap means less pressure on the players whereas less will give you a more desperate game.

What we found is that it mostly doesn’t matter.

There’s a degree of “auto-balancing” when it comes to combat because the players can retreat whenever they choose and once again, retreating is a d20 roll where you have a 75% chance of getting some level of success.

| Roll | Result |

|---|---|

| 20 | Perfect Escape. The group makes a perfect escape from the situation to any location of their choice within the Region Map and cannot be pursued. |

| 11-19 | Escape. The group makes a safe escape from the situation to any adjacent location of their choice within the Map and cannot be pursued. |

| 6-10 | Dangerous Escape. The group escapes to any adjacent location of their choice within the Region Map, but at a cost. They must make a Tough Choice related to the situation. |

| 2-5 | Failed Escape. The group fails to retreat from the situation and are pinned down. They cannot retreat and must fight it out to the end. |

| 1 | Disastrous Escape. The group retreats to an adjacent location of their choice within the Region Map, but at a severe cost. They suffer a Severe Setback and may be pursued. |

On top of this, whenever an enemy mech loses 50% of its structure, or the entire group of enemies loses 50% of their units, the individual/group makes a morale check, which can cause them to retreat in part or in full.

Over the course of our game, I also learned what should have been obvious: players are going to miss half the salvage you place, so it’s a little hard to place too much. On the other end of the spectrum, as long as they find the minimum amount for the crawler’s upkeep, everything works out. What you’re left with as a mediator is a wide gulf between extremes, so as long as you place salvage “as it would make sense”, it’s not going to disrupt the balance of the game.

friction points

Compared to Break!!, I was really happy with my Salvage Union experience. The game met the expectations I had, and while I was surprised about certain things, the game delivered the post-apocalyptic mech fantasy I was seeking. Collectively, our group found two friction points I think are worth noting:

- There is no half-measure

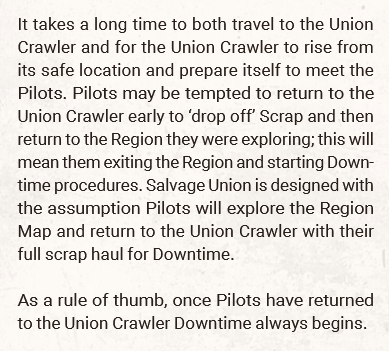

The obvious instinct for players (including myself) is to return to the crawler whenever you find salvage and deposit it so that it’s safe. The book anticipates this and specifies:

Whenever you go out on a salvage run, you stay until you’re ready for the next downtime to happen. Downtime takes a week, during which the region might change. This constraint requires a bit of suspension of disbelief, but it’s very understandable why players can’t safely deposit everything they find.

- You can waste a lot of prep time

The downside to the retreat rules and miss-able salvage is that you can waste a lot of prep as a Mediator. I spent a lot of time building out combat encounters that my players never encountered or saw and immediately retreated from. Obviously in a full campaign, these things can be re-used and might persist in a region between downtimes. Nonetheless, for what became a one-shot, it was unfortunately wasted work.

Ultimately I think that if I spent more time in the system, this would become irrelevant, as I could feel my familiarity growing overnight. It might have taken me an hour to build my first combat encounter, but by the end of the night, I needed 15 minutes. As I flipped back and forth through the book, I started memorizing the mech components and felt comfortable throwing together custom patterns.

We had a great time with Salvage Union, and it’s definitely a system I want to return to. The reason we stopped playing is because we realized that the only thing left in the system was time investment. AstralFrontier gave a really good example: the Engineer has a capstone ability where the crawler no longer has to pay upkeep. Even if we played more games of Salvage Union at higher levels, we wouldn’t really appreciate how good that ability is unless we had spent a bunch of sessions where we had to pay upkeep.

Beyond the fractal dungeon, the game is about the journey, the struggle over time to persist in the wasteland. It’s about encountering a strong enemy and running away, only to return months later with stronger mechs. Without that intermediate struggle, the destination loses its payoff.

If that sounds like fun to you, I highly recommend you give Salvage Union a shot.