I keep avoiding the elephant in the room: I really haven’t said anything about The Serket Hack’s combat system. I know the vague shape of it, but my ambition to have unique character classes means that I don’t have a lot in the way of details. As previously mentioned, there are sixteen paths that players can pick from, but everyone starts out as a Fighter. This is directly inspired by Lancer, which has all players begin using the same starter mech (the GMS Everest). Despite being a starter mech, the Everest is an extremely powerful all-rounder effective at all levels of the game. It’s not flashy, but it’s extremely flexible and has abilities to improve its action economy and no real weaknesses.

My goal with the Fighter is to provide a solid foundational standard for players that can operate at all levels of the game. All other classes are a departure from the basics established by the Fighter — some of them have entirely different core resolution — but all of them ultimately balance around the same standard. Before I can even begin talking about how the Fighter operates, we need to look at some of the base assumptions on how combat functions.

Approximating Space

My thoughts on the nature of space, locomotion, and positioning could fill another blog post (or two), so I’ll be saving that for a later date. The major impact on The Serket Hack is the idea that combat takes place via abstract representation. “Movement” and “Range” are not considerations in the same way they would be in a grid-based tactical game like Dungeons & Dragons. Lest I go on an extended ramble, let me clarify how this works with an example:

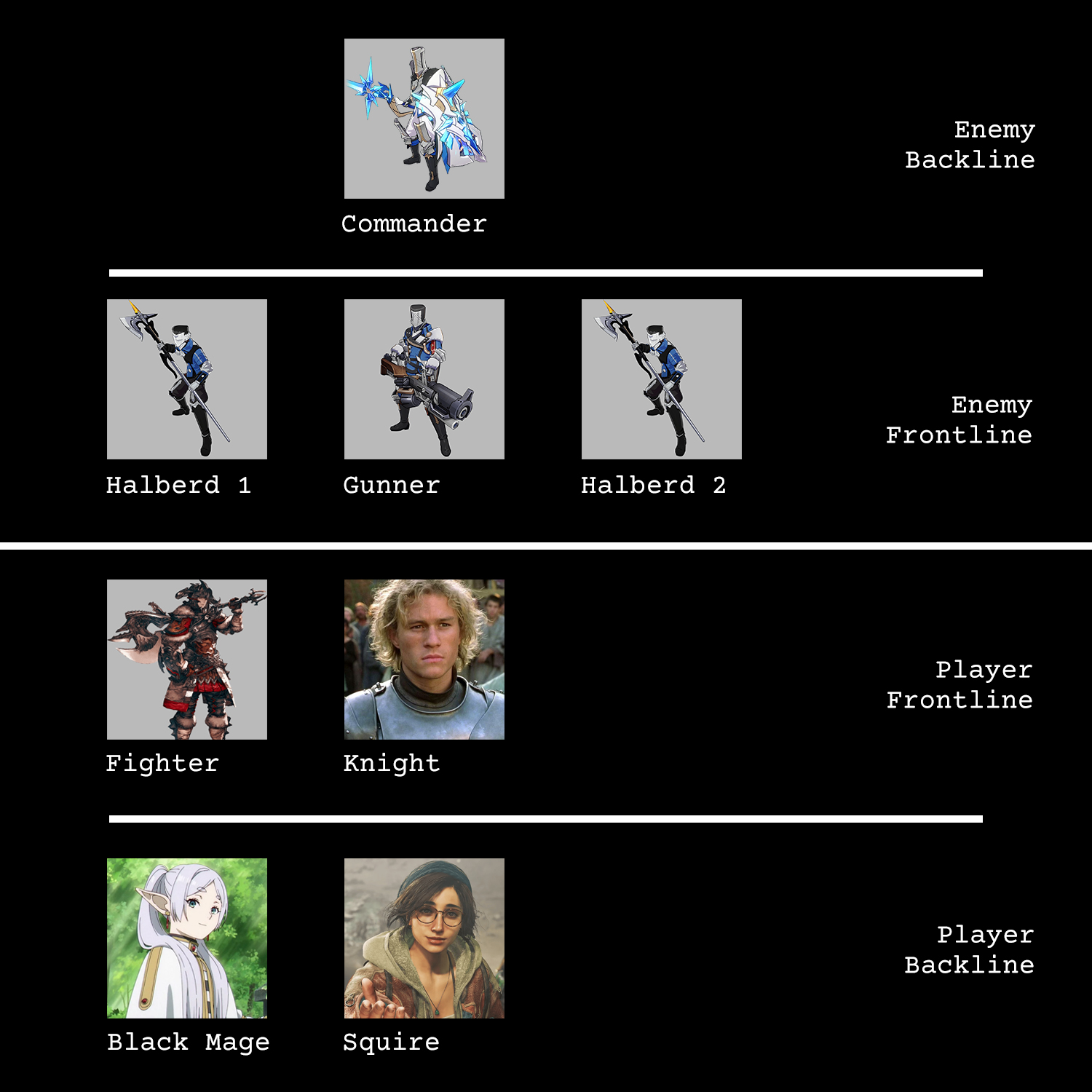

Everything in the battlefield is “roughly” one dimensional. We technically have a frontline and a backline, but these function more like special statuses than representations of physical space. When it’s the Fighter’s turn, they simply declare an attack against Halberd 1 without having to worry about positioning. The Black Mage casts a fireball targeting the Gunner, which deals splash damage to adjacent characters — affecting Halberd 1 & 2. Notably, the Commander is unaffected by the splash damage on the backline. Characters on the backline are never considered adjacent to any other character, including other backline units. They may only be targeted by ranged attacks or attacks which target “all enemies”. If there are ever no characters in the frontline (on either side), all characters in the backline move to the frontline.

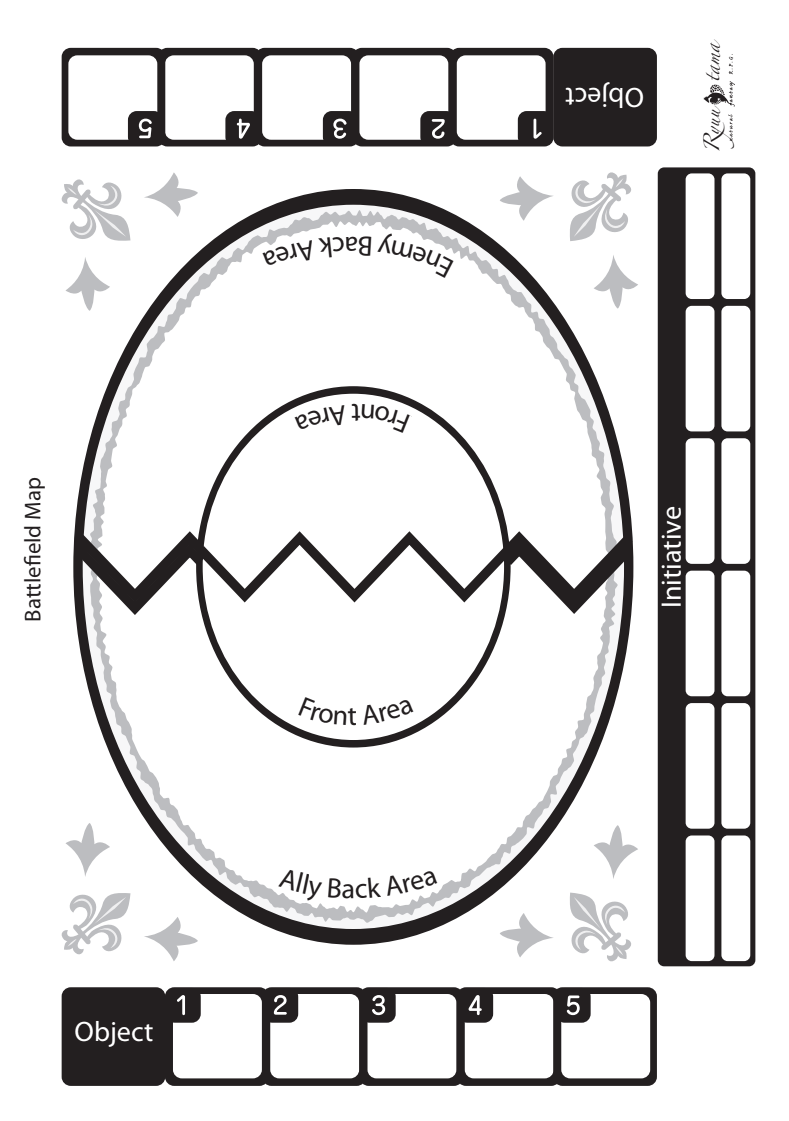

Those of you familiar with the game Ryuutama may recognize that this system is deeply inspired by the battle egg:

When we abstract this way, it becomes clear that we are unconcerned with a perfect simulation. This is combat-as-sport, and definitely not combat-as-failstate. Dwiz over at Knight At The Opera wrote a post talking about genres the OSR can’t do, and there’s a moment where they discuss Wuxia:

Characters fight when they’re enemies, when they’re friends, when they’re strangers, when they’re teacher and student, when they’re trying to recruit one another, when there’s been a misunderstanding, when they’re practicing, when they have an audience, when they want privacy, when they’re eating, when they’re shopping, when they’re on the road, when they try to meditate, when they’re flirting, when they’re outnumbered, and on and on and on. Any time you ask yourself, “could this be a fight scene?” the answer is probably yes. It is not merely the perfect solution to nearly all problems. Characters resort to it even when there’s no problem. It’s often casual, accidental, and even friendly.

While The Serket Hack is not entirely a Wuxia game, this is the sort of energy I’m chasing when it comes to the stakes of combat. Players can expect combat encounters any time they walk into the tall grass or make eye contact with a rival Fighter. It is simply the nature of their existence as violent actors.

Anatomy of Attack

Inheritance: Total//Effect

The foundation of Fighter mechanics are based on the Total//Effect system by Binary Star Games, though I am taking a rapid departure from convention. Within the T//E system, players roll 3d6 and sum them to get the Total. Based on that total, players will use the Low, Mid, or High die as the Effect die. Using an example from Binary’s Valiant Horizon game:

My ranger uses the move “Snap Shot”, and I roll 3d6 = [5, 3, 6] for a total of 13. Snap Shot deals Low Die Weapon Harm (3), however on a total of 13-14, it deals Mid Die Harm instead for 5 damage. If I had rolled a total of 15 or higher, it would deal High Die Harm for 6 damage.

Evolution: My Hacky Bullshit

I like the fundamentals of T//E, but there are a lot of base assumptions and subsystems it provides that I’m ignoring. Most significantly: the T//E system uses a range band system to represent space. For example, the Snap Shot ability deals damage at Near (one space away) or Far (two spaces away). This is why I started by explaining the way The Serket Hack sets up a battlefield. Furthermore, abilities (at least those in Valiant Horizon) are extremely self-reliant: the target numbers are attached to the moves themselves, and they never change. This is intentional on Binary’s part — the goal of Total//Effect is to reduce the amount of “processing” in a turn. While I agree with the sentiment, I like having enemies that are easier or harder to attack.

Enough preamble. What does it actually look like when a Fighter attacks in The Serket Hack?

- The Fighter declares an attack against Halberd 1 using their battleaxe.

- Roll 3d6 = [1, 5, 4], Total = 10

- Halberd 1 has a Defense of [9, 12]. This value is public knowledge, known to the players.

- Because 10 is greater than 9 but less than 12, the Fighter deals Mid (4) weapon damage.

If the Fighter had rolled an 8 or less, they would have dealt Low (1) damage. On a 12 or higher, they would have dealt High (5) damage. Unlike Valiant Horizon, whose thresholds and damage are tied to the move, all characters use the same Defense targets which dictate Low/Mid/High.

This post was meant to go into detail about Fighters specifically, but we had to build out a lot of combat foundation first. In fact, we’re not done with the foundation — I still need to talk about player health — but it’s going to have to wait for the next post, where I’ll continue unpacking the Fighter by talking about the vision for the class, its non-combat role, and some core characteristics that separate it from other classes.